Research Background

Psychologists have been interested in the ‘nature vs nurture’ question for over a century, with answers to this question becoming increasingly complex as we develop a greater understanding of how these two sources of influence interact. However, this complex interplay (akin to the balance between yin and yang) is not always recognized by either parents or practitioners. For example, when a child has a problem, parents often blame the child, while professionals often blame the parents. Developmental science shows that answers need to include not only both child and parent, but also ‘neurons and neighbourhoods, synapses and schools, proteins and peers, genes and government’ (Sameroff, 2010, p7).

Personal change (e.g., Piaget’s developmental stages, or growing language skills)

Context (e.g., widening social horizons when children start school)

Regulation (e.g., from physiological to psychological to social)

Representation (e.g., acquiring a theory of mind)

To span all four of these models, our study includes individual assessments of children, measures gathered from parents and teachers, including speech samples and direct observations of children and parents in goal-directed play. This multi-pronged method is important because, as children grow up, they become better able to regulate their own thoughts, feelings, and actions. ‘Other’ regulation also becomes more mixed, as children start to learn from peers and teachers. Our work also recognizes the importance of context. For example, we know that young children will develop their self-regulatory skills more quickly if those delivering ‘other’ regulation (e.g., caregivers, teachers, peers) can ramp up and roll back support in a dynamic way, to always give just the right level of support.

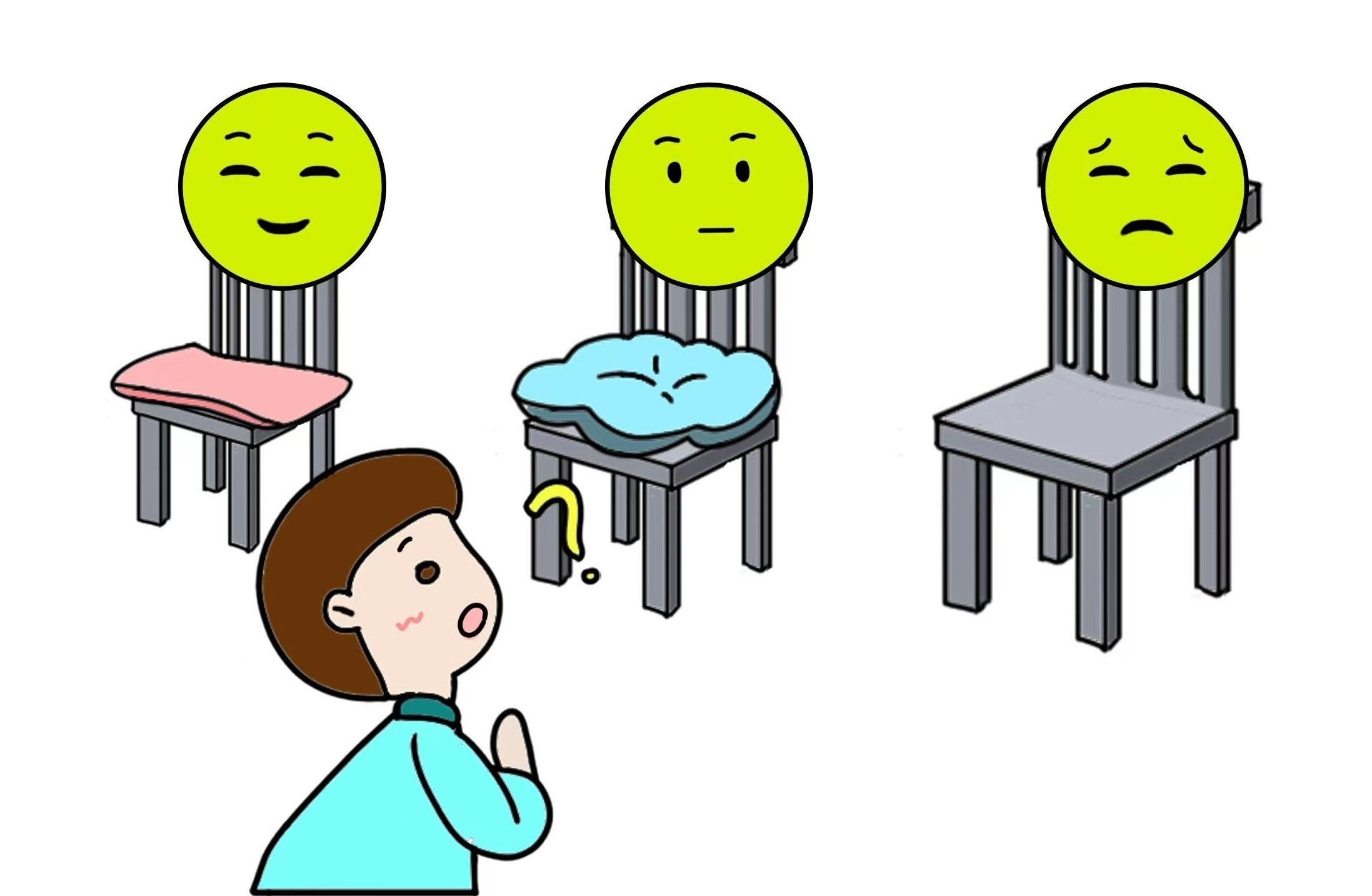

1.We can call this ‘Goldilocks’ support,

after the fairy story about a little girl who visits the house of three bears and tries out different things (chairs, bed, porridge) until she finds what is ‘just right’. In this story, Goldilocks is often presented as quite naughty, in that she is using other people’s things without permission. But we could also say that Goldilocks is showing lots of initiative, in actively seeking out things that meet her needs perfectly. Thus, a key tenet of this approach is that children play an active role in their own development.

2. Are you a ‘Carpenter’ or

a ‘Gardener’ ?

styles of parents and teachers(Gopnik, 2016)

Both the carpenter and the gardener invest lots of time and care in their work. However, whereas carpenters have exact plans for the wood in their workshop and can repeat this plan many times with the same results (a fine set of chairs, for example) gardeners know that seedlings vary and so need bespoke care. Some plants love full sunlight and others prefer dappled shade; some plants will grow straight as an arrow, others need support to grow straight; some plants are hardy, others need protection from the frost. But all are beautiful and rewarding to grow.

It is no coincidence that many countries use the German phrase ‘Kindergarten’ (children’s garden) to refer to places of learning for young children. This approach teaches us that:

What works will vary from child to child – and, for any one child, what works will change over time, so parents and teachers need to be very flexible.

Happy children are better learners: just like ensuring that a plant has enough sunlight or water, so meeting children’s emotional needs provides a valuable platform for development.

Plants have flowering and dormant seasons; likewise, children’s ability to ‘display’ their strengths will vary over time. Expecting children to constantly be in top form is unrealistic - remember, dormant periods are necessary for growth!

Getting a ‘child’s eye’ view of their worlds can change how you approach your child’s life – leaving time to smell the flowers, for example…

When there is a culture of “winning at the starting line”……

It is hard to allow children to grow at their own pace and follow their own interests

We hope our study will be a catalyst for culture change, fostering awareness of the importance of young children’s social and emotional wellbeing and highlighting the close links between wellbeing and academic achievement. Specifically, our study has the following aims:

Connect the viewpoints of parents, teachers, and children, putting children’s perspectives in the foreground, and tracking whether differences in viewpoints increase or diminish as children progress from Y2 to Y3 of Kindergarten.

Understand the importance of home-school connections – by applying novel wearable devices to gather automated recordings of children’s linguistic environments and exploring how the frequency and contingency of family talk contributes to individual differences in children’s school readiness.

Examine cultural influences at multiple levels – by comparing children in Hong Kong with their counterparts in the UK and in Mainland China – and by looking at contexts linked to different outcomes within Hong Kong (e.g., local vs international schools, and across classrooms that differ in ethos).

Demonstrate the way in which social and emotional well-being can foster academic progress – even if this means that some milestones (e.g., piano exams) are considered as optional rather than compulsory.

Gardening Appraoch

In HK, can we give children a head start without pushing them too hard?

A case study of Luca

Of course, the pandemic has made developmental research very challenging – not least because our top priority is the safety of children, families, and teachers. At a practical level, our aim is to be as agile and flexible as possible in our research methods, whilst maintaining high standards in data-collection and analysis. Thus, if in-person and remote testing methods must be combined, we will need to demonstrate that each approach yields equivalent results. Likewise, we must assess the validity of measures designed for UK families before applying them in Hong Kong.